The Theory of Everything

The Theory of Everything

Starring Eddie Redmayne, Felicity Jones, Charlie Cox, Simon McBurney, David Thewlis, and Emily Watson

Directed by James Marsh

Rated PG-13

Run Time: 123 minutes

Genre: Biography/Drama

Opens November 14th

By Eric Forthun of Cinematic Shadows

The Theory of Everything showcases Stephen Hawking in an unfamiliar way for most people: as a young, ambitious, extraordinarily intelligent man who falls in love and lives a blissful, remarkable life with multiple children. Only when the story falls into the recognizable part of the narrative does the film become a different specimen, exploring Hawking's experience with ALS and how his wife grows increasingly distressed with her own life while trying to balance his inability to work within his own. The performances at the heart of the film define the effectiveness of James Marsh's vision: Eddie Redmayne is a dead ringer for Hawking and delivers arguably the most pitch-perfect performance of the year, while Felicity Jones provides a sustained, nuanced, and humanistic performance that underlies the tragedy of Jane Hawking and her undertakings as a wife, mother, and student. They are extraordinary and compassionate characters that elevate the occasionally melodramatic material into a universally affecting, beautiful piece of work.

The story starts with Stephen Hawking's (Eddie Redmayne) studies in England during his college years. He's clearly the brightest of his year who carries plenty of quirks, making him a man that connects with some and puts off others. Yet he spots a lovely woman named Jane (Felicity Jones) at a party one night and eventually asks her to a dance, where they share their first kiss and spur their everlasting love. Jane is starkly different from Stephen, namely in that she believes in God while he believes in science, something that he stands by and points to analytical proof as a means of explaining his beliefs. Yet she argues that they are just that: mere beliefs that rely on the basis of scientific findings by men, much like his claim that religion was created by man. Jane proves to be an intelligent counterpart in Stephen's eyes due to his respect for her work; she studies ancient poetry and cultures with both seemingly having no idea about how the other does the work they do. There's something about the compassion that they show for one another that makes his growing struggle with a terminal disease all the more tragic.

Hawking is given two years to live and considered a lost cause in the doctor's eyes. His brain function won't actually be affected by ALS, meaning that he will be just as intelligent as ever, but his motor functions and ability to speak and communicate with others will be hindered permanently. Whereas many biopics would overload the audience with Hawking's struggles, Marsh's film tenderly examines the ramifications of such a devastating disease on both the person affected and their loved one. The story uses this dual balance to great emotional effect: Jane's story is given equal weight as she acts as a co-lead alongside Stephen. Her exploration of self alongside her husband's deteriorating physique remains the more affecting and resonant story in terms of its tragedy. Take for instance, a beautifully embattled scene where she takes up a camping trip with a close friend, Jonathan (Charlie Cox). They go with her children for a getaway while Stephen stays at home with a caretaker; as Jane looks at Jonathan putting together the tent and seeing the children's excitement, the camera lingers on her face. Her pain pushes through her façade as she realizes that Stephen will never be capable of such actions.

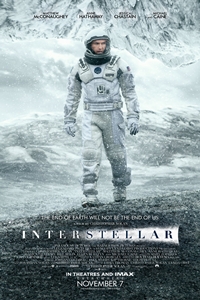

Their love pushes them through turmoil, tragedy, and the likes of which no couple should ever have to see. There are certain ideas on display that connect to other prestige players in 2014: Interstellar's lofty ideas surrounding space travel and the effect of relativity and The Imitation Game's look at ambition and the way a person attempts to overcome tragedy in their personal life come to mind. Director James Marsh has the ability to explore grand ideas with a deeply personal touch: his documentary Man on Wire is a towering achievement that plays like a heist film with a charming real-life lead, while his subdued 2013 thriller Shadow Dancer delivers strong performances alongside a detached, harsh view of British society. He tells his most compassionate tale here, with the help of Jóhann Jóhannsson's delicately layered score and Benoît Delhomme's lusciously intricate cinematography. Redmayne's transformation is undeniably the finest work of his young career and recalls other brilliant, transformative works like Daniel Day-Lewis in My Left Foot and Leonardo DiCaprio in What's Eating Gilbert Grape?; it will receive Oscar attention this February, as will Jones. While their story uses minor familiarity in its conversations surrounding love, its juxtaposition alongside Hawking's real-life ideas make the film a unique, emotionally ravishing romance.

Rosewater

Rosewater

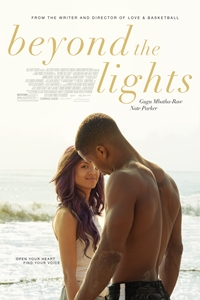

Beyond the Lights

Beyond the Lights

Dumb and Dumber To

Dumb and Dumber To

Laggies

Laggies

Interstellar

Interstellar

Revenge of the Green Dragons

Revenge of the Green Dragons

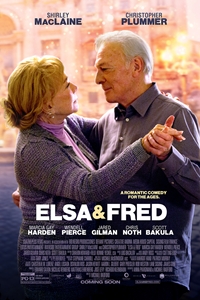

Elsa & Fred

Elsa & Fred

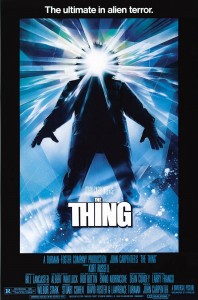

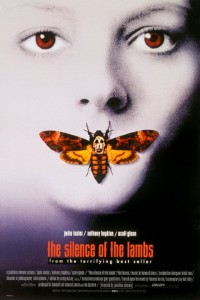

For a horror fanatic, asking them to pick their ten favorite horror films can be a difficult challenge. So today, here are ten of my personal favorites. Enjoy!

For a horror fanatic, asking them to pick their ten favorite horror films can be a difficult challenge. So today, here are ten of my personal favorites. Enjoy!

Top 10 Horror Films

Top 10 Horror Films Top 10 Horror Films

Top 10 Horror Films

Nightcrawler

Nightcrawler

Force Majeure

Force Majeure

Camp X-Ray

Camp X-Ray

Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)

Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)